Post by VWCA_Adman on Jul 20, 2022 13:34:32 GMT -6

Comparing build quality from two yesteryear survivors

Comparing build quality from two yesteryear survivorsBy Cliff Leppke

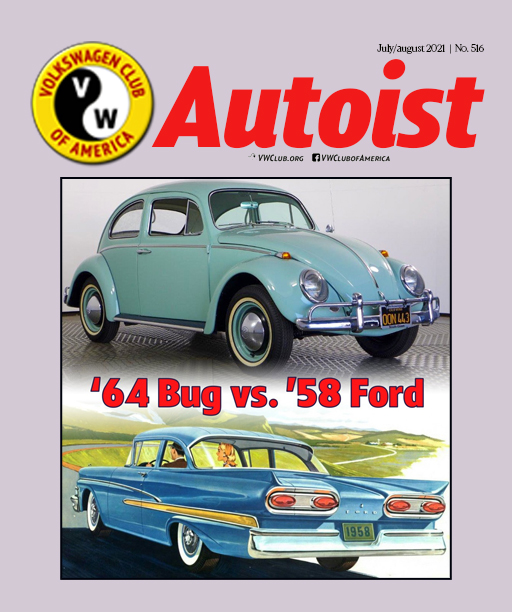

You’ve seen the glamorous collector car magazines. In their glossy photo spreads, fabulous 1950s Detroit dishpans sparkle like flawless gems. Editors gush with unchecked enthusiasm for these Eisenhower-era driveway dinosaurs. Their outrageous styling, excessive length and dubious handling strike collectors as desirable because they are, say, distinctive. The truth is many of these insolent chariots appeared awfully alike — the same finned cantilevers in back and chrome dripping on the sides.

Sure, some zigged and other zagged but within a corporation’s lineup the basic body shape, greenhouse and the like were monotonously similar. Just feast your eyes on the 1959 Flat-Top GM jet-age fetishes — the sameness is there from top to bottom. A bag of M&M’s has more variation. For something completely different in its celebrated year-to-year sameness, postwar Americans flocked to the anti-styling VW Beetle.

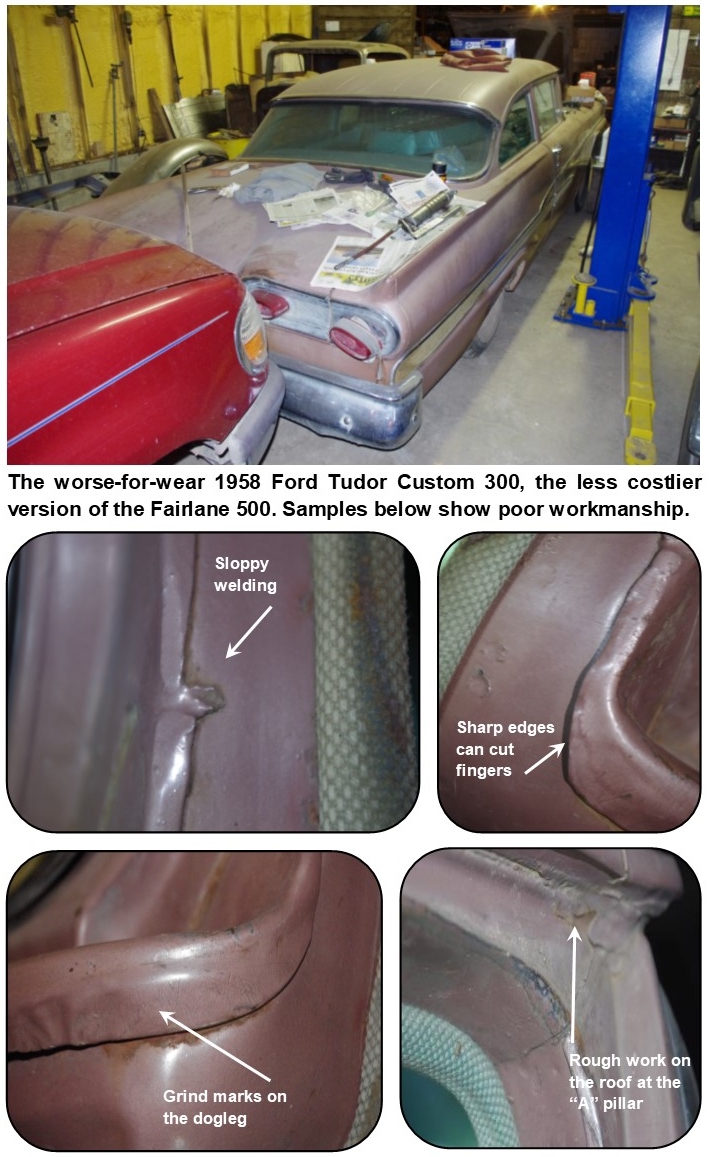

At a distance, Detroit’s cantilevered autos shocked sensible eyes. What happens when you get a closer look? Do you find good ergonomics and careful build quality? The answer requires one to put down the magazines and actually inspect survivors — untouched examples from the conformist Age of Anxiety. I headed to the Leppke farm for that closer look. Behind one barn door you’ll find a 1958 Ford Custom 300, Bali Bronze over bright vinyl triple-tone emerald green with color keyed box-striped nylon. This untouched survivor has several built-in disasters due to styling for style’s sake and slipshod assembly.

At a distance, Detroit’s cantilevered autos shocked sensible eyes. What happens when you get a closer look? Do you find good ergonomics and careful build quality? The answer requires one to put down the magazines and actually inspect survivors — untouched examples from the conformist Age of Anxiety. I headed to the Leppke farm for that closer look. Behind one barn door you’ll find a 1958 Ford Custom 300, Bali Bronze over bright vinyl triple-tone emerald green with color keyed box-striped nylon. This untouched survivor has several built-in disasters due to styling for style’s sake and slipshod assembly. My grandparents bought the 1958 Ford Tudor, opting for the less costly Custom 300 series rather than the flossier, longer Fairlane 500. The latter had two inches more wheelbase and more expressive rear quarter panel swag lines. My grandfather made two apparently contradictory deviations from the standard car: He bought the optional four-barrel carb, 332-cubic inch, 265-hp Interceptor V-8 and mated it to a three-speed manual transmission with electric overdrive. Chances are he wanted reduced engine wear due to overdrive’s taller top gear rather than fuel-sipping transport. He later added an air conditioner and covered windows with Venetian blinds — all meant to cope with scorching North Dakota summers.

My grandfather, according to local legend, wanted to make a serious headway against North Dakota’s headwinds. He eventually retired this ride in favor of a 1969 Caddy. Then, he ditched that monster for a diesel Olds — after the 1970s fuel crisis. The double nickel federal speed limit cramped my grandpa — my grandma enforced the law. She’d crain her neck, spy the speedo and say, “Arnold you’re driving too fast.” You’d think the nagging checked marital bliss — but I noticed my grandpa often turned down his hearing aid — clever.

My 1964 VW Beetle, in contrast, has just 40 ponies and a leisurely top speed of 72 mph —headwinds really cut its progress. But it’s thrifty. And it’s also a survivor. The cars differ in design, assembly quality, mechanicals and ease of use. One thing they both share is a shift toward bright insides due to vinyl upholstery and door card treatments.

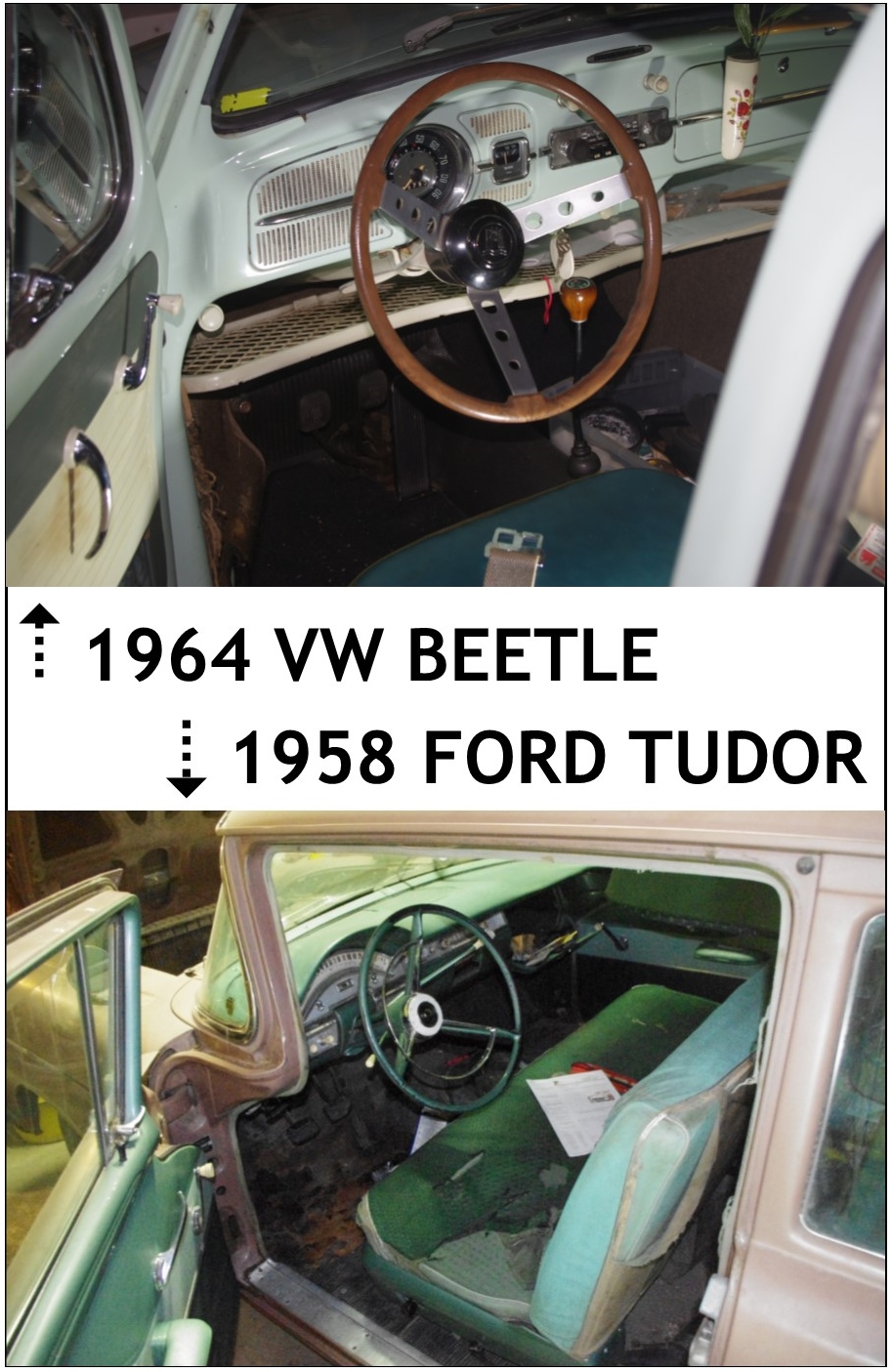

My 1964 VW Beetle, in contrast, has just 40 ponies and a leisurely top speed of 72 mph —headwinds really cut its progress. But it’s thrifty. And it’s also a survivor. The cars differ in design, assembly quality, mechanicals and ease of use. One thing they both share is a shift toward bright insides due to vinyl upholstery and door card treatments.The Ford’s more flamboyant; the Beetle more business-like. There’s more rug in the Beetle as the Ford uses faux carpet molded rubber-like flooring, whereas the Bug has grooved rubber mats with bound charcoal carpet trimming on the kick panels. The Ford’s got cardboard-like materials under the dash. The Beetle is very tidy under the metal dashboard, whereas the Ford is a festival of uncovered nasty bits but has a padded dash cover and plenty of instruments.

Entering the cars is an exercise in difference. The Ford’s wrap-around windshield apes a fiberglass Glastron Seaflite speed boat with the steering wheel on the left but results in a nasty dogleg for an “A” pillar. Ford did lots of trick stuff to compensate for this nautical affectation — troughs and weather-stripping routed water from the windshield to holes in the doors for drainage. Egress is just plain awful as the protruding glass requires a gymnast’s limber body in order to slide into the front seat without punching yourself in the gut. Happily, Ford’s front seat has a height adjuster. The Beetle’s front seats have three different back rakes. For 1960, Ford crowed about its latest invention for automotive egress — no doglegs. Surely, Detroit discovered its obsession with wrapped glass but like some film franchises, went too far.

The Beetle in contrast requires deft footwork, as space between the front seat and the door pillar is tight. The Beetle’s upholstery didn’t hold up very well, it came apart at the seams — stitching failed — and the vinyl split. The covered Ford seats — Grandma never let us ride on the car’s nude fabrics — fared better. VW later rectified the short-life upholstery with a durable basketweave design.

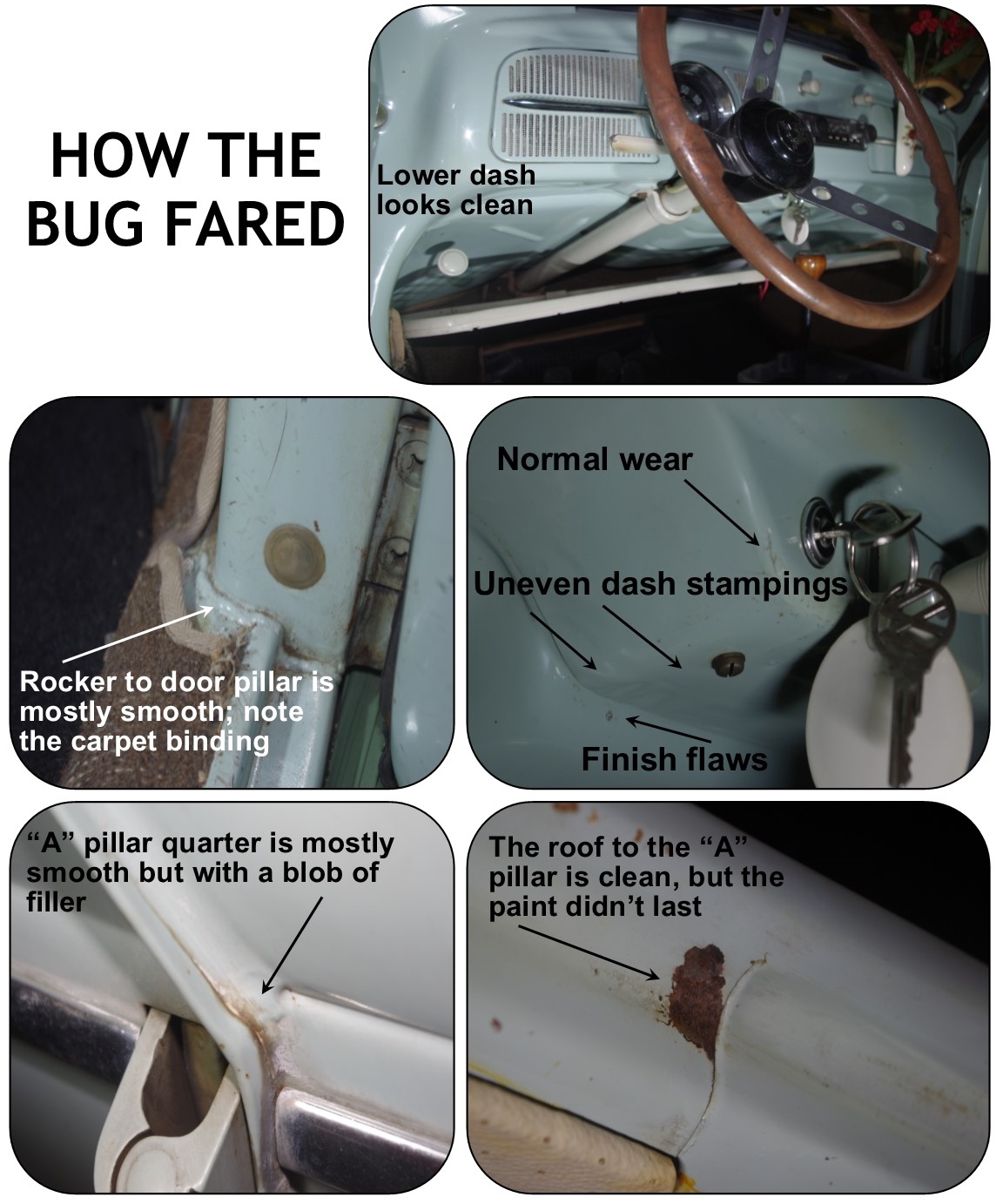

Bodywork reveals a big gulf between the two cars. The Ford’s got a legion of sloppy body prep and sagging paint. The Beetle in contrast is a smooth operator except for the area under the dash, where you see paint flaws.

Don’t look too closely at the Ford or dare to caress it without split-leather work gloves. There are lots of grinder gouges and filing hashes plus plenty of sharp spot welds or spatter surrounding the front doors from top to bottom. And the body wavers where pillars attach or on the catwalks. It appears they rushed this one out of the factory with little thought that length alone didn’t make a quality car. Ford’s fine family of vehicles wasn’t for discerning families.

Photos reveal the gaffs. Notice the weld spatter, buckled panels and unsightly grinding or file marks. Let’s look at that rakish windshield from the backside at the top. Notice the unlovely marriage of roof to pillar. The mess doesn’t stop there. Check the area near the B pillar — a similar mess. Sagging paint flows down the dogleg. Don’t touch the spot welds as they’re very sharp. At the windshield’s base, grinding and filing didn’t smooth out the panel. Notice the ugly assortment of welds where the dogleg transitions to the lower door cutout. And can you justify the wrinkled metal on the rocker panels or rear quarter panels? It appears as if the styling department stretched metal sculpture beyond the capacity of the stamping outfit to make these shapes. Sometimes there are large gaps between adjoining body sections.

Photos reveal the gaffs. Notice the weld spatter, buckled panels and unsightly grinding or file marks. Let’s look at that rakish windshield from the backside at the top. Notice the unlovely marriage of roof to pillar. The mess doesn’t stop there. Check the area near the B pillar — a similar mess. Sagging paint flows down the dogleg. Don’t touch the spot welds as they’re very sharp. At the windshield’s base, grinding and filing didn’t smooth out the panel. Notice the ugly assortment of welds where the dogleg transitions to the lower door cutout. And can you justify the wrinkled metal on the rocker panels or rear quarter panels? It appears as if the styling department stretched metal sculpture beyond the capacity of the stamping outfit to make these shapes. Sometimes there are large gaps between adjoining body sections.This pictorial essay shows the mistakes collector-car photo spreads never reveal. At fancy car shows, these machines are so well prepped, there’s no evidence of these known eyesores on wheels. And 1958 proved particularly difficult for Dearborn, as its Edsel variation of what you see here was an onslaught on consumer senses. Don’t let anyone fool you into believing only the Edsel came off assembly lines rife with defects — this Custom 300 is proof. Yet, this car racked up lots of miles as a useful if blemished servant.

The VW in contrast has fewer obvious mistakes. Yet, it’s not as perfect as those famous ads promised. The “A” pillar is smoothly shaped and richly coated. Rocker panels are likewise smooth. Most welds are neatly completed, although you’ll see some unwanted crud under the paint near the door pillar. And the door’s weather-stripping abraded the transition from roof panel to pillar. The biggest gaff is ahead of the ignition switch. There is a bubbled area where the dashboard meets the abutting panel. Clearly all those inspectors who signed off on that Beetle’s exterior in the famous ad, where blindfolded — not pegging an obvious blemish. The transition from front quarter panel to “A” pillar isn’t blotch free either.

In sum, VW wins this contest of mass-produced automotive aesthetics. Its body design is better suited to rapid metal crafting. It’s finished with greater care, too. Yet, it’s not perfect — just far fewer flubs than the fabulous ’50s Ford.